Assumption Mapping – Deciding where to start

When creating new product capabilities, we quickly tend to get lost in research or implementation

Most teams, and especially their product managers, are approached multiple times a week with feature ideas or customer problems to solve. Remember the last time this happened to you? What was your natural reflex?

Stop implementing first ideas

Unfortunately, many teams (and their leaders) jump directly to implementing solutions. They think the problem is clear, and everybody has a shared understanding of it. And, of course, they want to fix it as quickly as possible. My theory is that this is natural human behavior. Our reflexes are to be helpful, solve problems, and come up with ideas. We see something and directly react with a solution because it is the shortest route.

However, there are better options for creating successful products than following this reflex. Have you ever shipped a feature or created something based on your (or someone else's) first idea? Do you know if that worked out? Did People want it and can use it? Or, even before shipping, was it easy to implement your idea, or did you get lost in complexity while 'just creating it'?

That's why we want to vet and test our ideas before investing further in them. Ideas are loaded with assumptions, biases, theories, and beliefs — usually, not just one but many of them.

Deconstruct your problem

So, let's start to deconstruct the idea. But before directly jumping into the solution, clarify the problem. Can you clearly express the problem? Do you know the underlying motivation of the user? Is this a problem for many or a few? Is this constant, or will it go away automatically? What is the goal of your user and customer? What is their initial motivation? Leverage your existing material. Look at your journey maps. Look at former research. Collect all these aspects down on stickies.

If you struggle to come to terms with differentiating between the idea, the problem, the goal, and the motivation, you can backtrack from the idea back to the motivation like this:

Deconstruct your business impact

Continue to consider why it makes sense to approach this from your business perspective. What impact do you expect? What indicators are you trying to influence? What effects do you expect regarding the mechanics of your business model? To make it easier to identify these, look at existing artifacts. You may have a KPI Tree, an Impact Map, or other business model artifacts. Again, collect relevant aspects on stickies.

You can do this alone but will most likely work with a team. Involve them to ensure everybody is on the same page about the problem and the expected business impacts. Make sure you are discussing the same thing, but don't start discussing deeply different solutions or what exact impact this might have. Remember, the goal is to collect assumptions. You don't want to argue without any insights. It is pretty pointless, and you only waste your time battling over opinions.

Deconstruct the idea

If you have collected aspects of the problem, move on to the initial ideas. People usually have at least one idea in their heads. Deconstruct these ideas a bit. What do you expect the user will do differently with this idea? What technology is needed? How do you imagine creating this? Don't go into too much detail at this point, but try to get out what people already are crunching in their heads on even more sticky notes.

Let’s be true to ourselves — most of these are assumptions

Now, you should have quite a variety of notes describing the customer problem, connected business aspects, and first solution ideas. The goal is to get it all out. You and everybody involved will have a lot of things in their heads, and you want to get an overview.

Since most statements on these stickies come from the top of the head, are borrowed from similar things, and are theories and ideas, we can call them assumptions. Call this out; it is not bad, nobody's failure, but rather a feature of the creative process.

The Assumption Map

Assumption Maps are a simple 2x2 matrix.

The vertical axis describes how important or critical it is that you got this thing right from Important to Unimportant. We believe this is the core of the problem. Is this a total show-stopper? Is it early in our journey, and people can’t move on if this fails? Is this the core of the idea, and if we miss this, nothing will work? Or is this a minor thing we will likely find an alternative? Even if this is wrong, it won't stop us from being successful.

The horizontal axis describes how much evidence you already have. From a lot of evidence to no evidence. To qualify the evidence, think about the different risks. How sure are you? Will somebody need this and give you money (or attention)? Will somebody be able to use this? Are you able to build and maintain this? Be true to yourself. Do you have hard facts because you already have this running? Or do you have the first indicators from tests? Or did you just hear about it in some interviews? Or is it your gut feeling, or somebody just brought that up, but you are not even sure what exactly it means? Is this technology you already created, or has somebody on the team created it elsewhere? Do you only think you can create this, but nobody knows exactly how?

Mapping process

Now, start populating this matrix. Go through your stickies and ask how important that aspect is and how much evidence you have. This will lead to discussions, which is fine. But concentrate on actual evidence instead of opinions. Does somebody have evidence? How strong is this evidence? Do you have significant proof, or is it a first signal? Start with your problem statements. If you are unsure if the problem you are trying to solve is worth solving, all your ideas won’t make a difference.

Try what sounds more accurate — Is it a "We believe that …" or is it more a "We know that …, because …"?

Reading the map and taking action

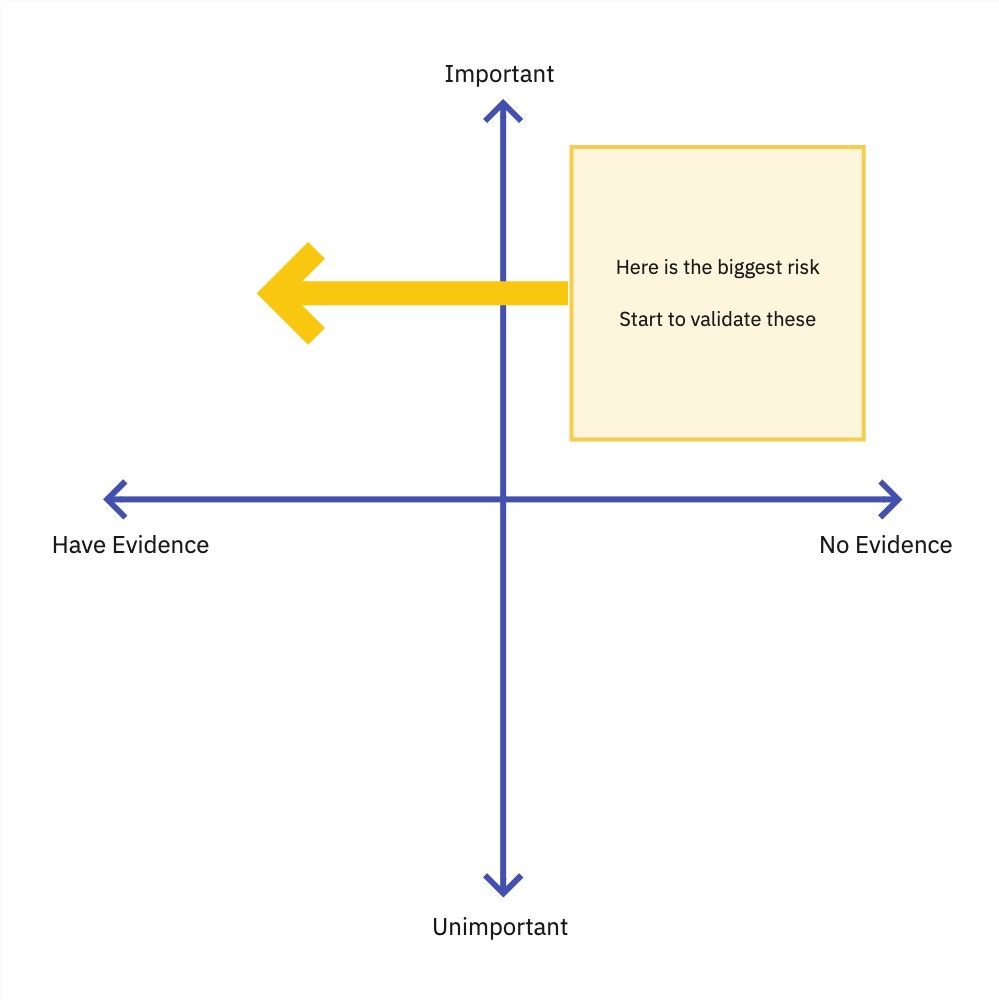

You want to start to de-risk the upper right quadrant, which contains the critical assumptions you don't know much about. The goal is to move from the upper right to the upper left. You want to start with the most critical assumptions because if they are wrong, everything else you do is not worth the effort to test.

Think in small experiments. I won't go into detail here on how to test these assumptions but think in the least effort to move the assumption to the left. Different assumptions will need different discovery methods. It may be okay for now to qualify this assumption in a conversation with some customers. You may need a small technical exploration, testing the workflow manually, or quantifying demand with a fake door test.

Keep your map updated

Keep this map updated to communicate what you learned and where you concentrate next. You may find that you are on the wrong trajectory and must discard this map. But more likely, you will find that you must change some parts of your problem definition or idea and approach to make this work.

Don't overthink it

At first sight, this method might sound like a big effort, but it shouldn't be. You can start mapping in a regular idea discussion. Call out assumptions and qualify how risky they actually are. The overall goal is to save time and money. Either you would get lost in testing everything and get stuck in research and discovery, or you would just jump to implementation. In both cases, you invested time in work, not creating any value.

Fit your investment into this approach to the size of your bet. Is this a big thing that requires much effort and has obvious uncertainties? Invest more. Is this a small thing? Don’t waste your time overcomplicating it; just do it.

I learned this method from Strategyzer's book Testing Business Ideas. They also published a public article on this method.